[Article originally appeared in Outdoor Painter]

If it’s not already on there, you might want to add Glacier National Park to your bucket list of painting locations.

I still remember my first glimpse of Glacier Park. I was 8 years old, and my intrepid grandfather let me ride shotgun on a month-long road trip through the American West. He spontaneously burst out in song as he rounded a corner on the park’s famous Going to the Sun Road, but I didn’t wonder why: Before us stretched a vista for which no photograph or park documentary could have prepared me. It took my breath away. Ridge after ridge faded into the blue distance, each line reflected perfectly on the glassy surface of St. Mary’s Lake. I tried to sear the view into my mind so I’d never forget it.

“Morning at St. Mary’s Lake,” by Kathleen B. Hudson, 2016, oil on linen, 14 x 18 in.

Inspired by that memory and last year’s “Timeless Legacy” exhibition of women artists in Glacier, I returned to the park last month to join 29 other artists for Plein Air Glacier, a festival hosted by the Hockaday Museum in Kalispell, Montana. We ventured into Glacier on June 25 for five days of painting.

The distinctive look of Glacier’s landscape struck me as a child, but I appreciate it even more now as a plein air painter. The valleys in the park are U-shaped, forming massive parabolas, because glaciers carved them wide and deep. (Rivers and streams carve characteristic V-shaped valleys instead.) The 150 glaciers that originally formed the mountainsides in Glacier National Park also left behind hanging valleys, which launch dramatic waterfalls like Bird Woman Falls hundreds of feet below during the summer melt-off.

Plein air artists always operate with a sense of urgency required by changing light and weather conditions. But to paint in Glacier is to be aware of time’s impact in a deeper way: Scientists predict that the 25 remaining glaciers in the park will melt and cease moving within the next 14 years. I reflected on this often as I wandered and painted in the park. As an artist I was bearing witness to the end of an era in this landscape: Glaciers, the active sculptors of this terrain for thousands of years, would soon grow still and vanish.

“Bird Woman Falls,” by Kathleen B. Hudson, 2016, oil, 12 x 9 in.

It was timely for me to hear Linda Tippetts emphasize the importance of action words in Native American place names as she led a demo at Running Eagle Falls. “I love that these names have movement in them,” she said. “After all, the elements in the landscape are always moving, never static.” That’s certainly true of the diverse landscape in Glacier Park, but artists have a limited window to capture some of the last glimmers of movement from the glaciers themselves.

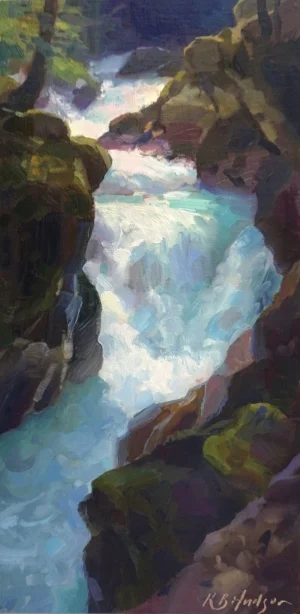

Painting at Avalanche Creek Gorge

Aside from Tippetts’s demo, I only encountered a few artists inside the park. (It’s a large place!) But California transplant Jeff Troupe and I found a common muse in the Avalanche Creek Gorge near one of Glacier’s most popular hiking trails. Meanwhile, artists Jeff Manion and Kenneth Yarus hiked deeper into the wilderness to capture views unseen from the roads. Manion noted that a bear passed by within a stone’s throw of his easel at one point.

On June 30, all 30 artists came into Kalispell to drop off work at the Hockaday Museum in time for the evening’s show and sale. Collectors turned out in droves that night; the museum hired a bluegrass band and catered the event while artists swapped stories about their adventures in the park.

"Early Light on Avalanche Creek Gorge," 16 x 8 in., oil

As the other artists and I took down some remaining paintings after the show, I found myself looking at the distant mountains and wishing I could head right back into the park the next morning. For me, there’s no clearer sign that a place has captured my imagination and sense of wonder.